Preface: Back in 2019, I was attending the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association in Toronto, and for reasons I don’t want to explain, I had to sell my book White Guys on Campus out of my roller bag. The academic homies kept calling it my “mixtape moment” because I would layout the books, sell to passers-by, while keeping an eye on hotel security. During this time, a longtime friend and colleague, Dr. Rosa Jimenez stopped by, but she did not simply buy book. She started hyping the text to other conference-goers while I was selling and signing copies.

Django Paris buying a copy of White Guys on Campus and trying to short me $0.01 😉 (L)

This was the first time I ever thought about the need for academic versions of a hip-hop hype person. I was extremely appreciative of Rosa, a badass scholar (check out this piece of hers on Community Cultural Wealth), and now it is my time to pay it forward. With this as context, I am taking Chicanostocracy in a new direction.

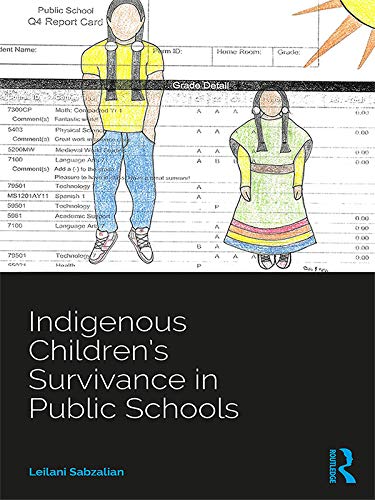

I’m a huge bibliophile, but I don’t sufficiently take advantage of opportunities to give public shouts out to writers who are holding it down – both in academia and in grassroots work. So, I am starting a new series called Academic Hype Man where I publicly give props to those who are doing the good work and, with respect to departed Rep. John Lewis, creating the “good trouble.” The first feature in the series is Dr. Leilani Sabzalian’s and her brilliant book Indigenous Children’s Survivance in Public Schools.

Let the Hype Commence!

- Author: Dr. Leilani Sabzalian (Alutiiq)

- Title: Indigenous Children’s Survivance in Public Schools

- Publisher: Routledge

- Paperback: 268 pages

- ISBN-10: 113838450X

- ISBN-13: 978-1138384507

- https://www.routledge.com/Indigenous-Childrens-Survivance-in-Public-Schools/Sabzalian/p/book/9781138384507?fbclid=IwAR2yud9XbR7ka4k3mapn7jhQvZrJCnMRvpFnckaDVrkeXBlfCKFLmD-9h8E (30% discount code: ADC21; Buy this book, dang it!)

Every year when awards season rolls around, I am usually disappointed. I am thoroughly aware that I am responsible for said disappointment because why would I expect anything different than results like:

- Driving Miss Daisy takes the Oscar over Do the Right Thing (1990)

- Macklemore beating out Kendrick Lamar for album of the year (Grammy’s, 2014)

To quote Conspiracy Brother from Undercover Brother, “Come on man! Even Cher’s won an Oscar! CHER!!!!!” The point here, however, is not to retread this old ground as many others have done extensive research on the best song/performance/movie/album rarely wins and there is usually a racial component to it.

Every once in while there is a Moonlight moment where a true product of genius gets its due despite pushes by massively over-hyped (usually White) works (see La La Land). Recently, I had an academic Moonlight moment when Alutiiq scholar, Dr. Leilani Sabzalian, received the American Educational Research Association – the largest academic educational association – 2020 Book of the Year Award for Indigenous Children’s Survivance in Public Schools.

Why was I so stoked about this recognition?

First, Leilani[i] is a tireless, fierce, and dedicated advocate for Indigenous education. She is both an assistant professor and Co-Director of the Sapsik’wałá Program at the University of Oregon – supporting the development of Native educators who will teach in Tribal communities. In short, Leilani is awesome and that should be reason enough right there!

Second, the text itself is brilliant as it contains both deep Indigenous education theorizing and is an incredibly engaging read. Theorizing through story telling is not only rooted in Leilani’s approach to research, but it is also an important reminder to readers that we are not simply talking about abstract concepts. There are the real lives of Indigenous youth, making the work all the more compelling.

Her work centers the lives of Indigenous youth as they navigate colonial education. Leilani does this by finding a very delicate balance. She does not want to center damage narratives or poverty porn of Indigenous peoples that have fascinated White anthropologist for years; however, she also does not want educators to think that supporting Native survivance is sufficient to support these students. As Leilani offered:

“My argument is that knowledge of Native survivance, settler colonialism, and Native students should be requisite teacher knowledge to counter deficit thinking, detect and interrupt settler colonial discourses in educational policy and practice, and image and enact anticolonial and decolonial educational alternatives in public schools.” (p. 14)

Yes, survivance is a strategy for navigating colonial education, but it is equally important to remember that our students only need to be resilient to the extent that their environment is toxic. The toxicity for Native students stems the historical legacy of and contemporary logics of colonialism, and Leilani demonstrates that effective teachers of Native students need to know and understand both survivance and colonialism.

This text is beautifully complex as Leilani walks the reader through the nuances of school life, doing a beautiful job of detailing the experiences of students such as Zeik and Celeste, as issues arise at school such as history units on the Pilgrims, “authentic” Native-ness, cultural appropriation/appreciation, and Native American Heritage Month. Leilani’s analysis is deeply textured and moves well beyond simplistic answers.

Leilani as a researcher is also ever present in the stories, giving advice to teachers about how to better support Native students. She continually deals with well-intentioned White teachers trying to support Indigenous students, being deeply critical of the harm they do to Native students while not being dismissive of their efforts either. There are many times in the text where Leilani walks the reader through incredibly difficult educational contexts, offering important advice to teachers trying to do the work, without turning herself into a type of decolonial superhero. Yes, Leilani is the expert in these educational spaces on Indigenous students, but she also does not paint herself as a person with all the answers.

I was also taken by the advice Leilani offered in the final chapter for teachers supporting Indigenous students, again demonstrating the incredible balance of the text. She describes principles that can be translated into educational policy, practice, and research, but without being prescriptive – avoiding the pitfall of “10 steps to decolonial education.” However, she also avoids another shortcoming of some critical work where the author does not offer any concrete suggestions.

On a perfect ending note, Leilani centers Indigenous cultural joy. As Bettina Love reminds in We Want to do More Than Survive, “We cannot freedom dream without joy. Abolitionists loved; abolitionists found joy in some of the most hideous conditions.” Leilani’s book makes the same case about decolonial education as so much of it is based on relations as she described watching Native students after a local pow wow they were hosting, “These students – once strangers – now felt like kin. Their joy was my joy, their being was entangled in my own” (p. 227).

In the final stanza of the book, Leilani describes watching the “tiny tots” dance as she started talking with a woman bearing visible bruises of physical abuse. They began talking and Leilani offered support and her cell number, and the two cried together. Leilani happened to be holding a whiteboard with the words, “Native love is…” as part of a project by the same name. The woman’s daughter finished her dance, and wanted to answer Leilani’s unfinished statement. Writing with a young child’s care and determination, the little girl wrote, “My mama.”

When you read that passage in the actual book, make sure you bring the tissues. If it doesn’t make you tear up, I’m not sure we can be friends!

This story demonstrates the essence of the book. Yes, there are horrible, inhumane circumstances Indigenous communities face; however, there is potential in collective agency to do something about them – especially in educational environments. Vivid descriptions of pain, love, loss, and communal joy make Indigenous Children’s Survivance in Public Schools a beautiful, important book in every sense. AERA made a great choice making this their Book of the Year in 2020, and my blog does not do justice to the text.

This is a really longwinded way of me simply saying, buy Leilani’s book, read it, apply it to your educational practice, and thank me later!

Peace,

NC c/s

P.S. I can already hear some of the homies talking mess with, “Dude, you’re a weak-ass hype man.” I get it. I really do, but “academic professional appreciator” just doesn’t have the same ring to it. So, please let me grow into this role, and support these really deserving folks in the process:)

P.P.S. Finally, if you want to be an academic hype person and write a blog post in this space, hit me up at chicanostocracy@gmail.com. I’m always looking for opportunities to lift up each other, and I am happy to open this space to genuine folks looking to do right by their crew.

[i] I’ve known Leilani for years, and it seems strange using formalities when addressing her. I absolutely understand that People of Color in general, and Women of Color in particular, continually deal with being referred to as “Mrs.” instead of “Dr.” In this blog space, the use of “Dr.” seemed too formal and impersonal. So, I am using Leilani’s first name throughout the blog. She is ok with this choice as I checked with her before publishing, but please do not read this as an invitation to be too familiar.