Prologue for the long read: It is not a secret that I really love the Flobots and their music. I remember being introduced to their song Handlebars during an interlude on Democracy Now! several years back and I was immediately hooked. Recently, their song Pray jumped into my top-10 anti-racist songs of all time because there are no other songs I can think of that contain the depth of social criticism regarding Whiteness that Pray has aside from Brother Ali’s Before They Called You White (also a dope track!!). I also included it in my list of anti-racist resources for this reason.

I played the song in my Whiteness and Education course thinking it could be an engaging pedagogical tool – especially with the intense imagery of the music video. Instead, after playing the song, my students were confused (maybe overwhelmed is a better description). We walked through the verses, unpacking individual lines and for some reason, they weren’t getting it. So, I started unpacking the lyrics.

I started to realize the song itself is extraordinarily dense, and I mean that as a very high compliment. What follows is a stream of consciousness reflection provoked by listening to the song on repeat during my morning walks and throughout my day. I hope this analysis has relevance for readers and is more than just an excuse for me to academically fanboy over the Flobots.

Enjoy!

When I first heard the song, I admittedly misunderstood the ideas articulated and intentions conveyed in the opening lines:

Pray the pale white devil back to hell

Blessed be my witness

Pray the pale white devil back to hell

Cry for my forgiveness

My misinterpretation had nothing to do with anything the Flobots offered. Instead, I was unintentionally rooted in the rightwing response to mass shootings where they continually offered “thoughts and prayers” instead of action. However, I soon remembered this was Flobots and not Sean Hannity, and it was important for me to remember that prayer and salvation can have productive functions within progressive social movements.

That is, liberation theology was at the center of Paulo Freire’s approach to education. A radical view of Christianity guided Dr. King, and Catholicism was the central to the United Farm Worker struggles. Unconsciously, I allowed rightwing folk to determine what is “truly pious” and began to give up on the productive possibility of prayer and religion, unintentionally ignoring, for example, the work of Reverend Barber contemporarily. It made me go back to Gomes’ (2007) The Scandalous Gospel of Jesus to remember Jesus’ radical humanist teachings, rooted not only in belief but actions.

This orientation in a radical humanism really struck me throughout the song. In particular, I have thought a great deal about the following lines:

Our weapon will not be righteousness

Our tool will be humanity

I loved this refrain for so many reasons. First, Christianity in a contemporary context is frequently framed as a form of righteousness, which pragmatically tends to be a destructive force as people continually strive to be more “holy than thou.” Again, this was a central premise of The Scandalous Gospel of Jesus whereby a competition toward fundamentalism has usurped the radical ethic of love that Jesus continually professed and enacted.

What was really interesting to me was not just the critique in the first line, but the solution offered in the second. So often, “battles” over racial inequality are framed in terms of “fights” which require “weapons.” The first line specifically challenged this notion as it should because using a weapon is a purely destructive force.

There is not the possibility to reclaim humanity with a knife or gun. This reminded me of the beautiful words of Michael Franti and Spearhead:

You can bomb the world into pieces

But you can’t bomb it into peace

Within this context, the second line offers a path forward. The idea of a “tool” is something that offers the possibility to create and grow and also loops back to the Flobots’s first album Fight with Tools. While it may seem a little idealistic, I was very much drawn to the idea of humanity as a tool. So much of systemic racism relies on a separation of people, a demonization of those not like us, and the method through this is forming radical, humanistic connections across difference.

This requires us to collective build, reminding me of what my colleague Dr. Roberto “Cintli” Rodriguez refers to as creation resistance.[1] This fostering of a greater collective humanity is a core issue because, as the song details, White supremacy has fractured our collective humanity as I will explore later in this meditation.

Returning to the beginning of the song, I have experienced disagreement with some of my friends about the meaning of the opening line of the song. One friend found the reference to the “pale White devil” to be relatively offensive, demonizing White people. I instead took it as an analysis of systemic racism. If my interpretation is correct, then there is nothing offensive about the phrasing because a) systemic racism does benefit White people and b) it is an inherently evil and unjustifiable system.

I was reminded of the distinction that critical scholar Zeus Leonardo made between Whitenessand White people (2009) offered, “‘Whiteness’ is a racial discourse, whereas the category ‘white people’ represents a socially constructed identity, usually based on skin color… Whiteness is not a culture but a social concept” (pp. 169-170).

While it may make White people feel uncomfortable to have this system explicitly labeled “White” – frequently leading to reactions that mirror what DiAngelo (2011) refers to as White fragility – it is important to appropriately label these systems. To the extent that White people have and continue to benefit from systemic racism, their discomfort is a mild price to pay. Additionally, I found it interesting how the song started from the perspective of Whiteness when the Flobots offered:

When the demons beckoned me to come

Why did I believe them?

Named my brother as three fifths a man

Left his body bleeding

There was a lot for me to unpack in these four short lines. From a critical Whiteness perspective, this really resonates with the historical formation of Whiteness. That is, in colonial (stolen) America, there was not a thing called “Whiteness.” Rather, people of European decent were known by their country of origin. A massive tipping point was Bacon’s Rebellion whereby a multiracial coalition of white and Black farmers led by Nathaniel Bacon defied Virginia governor William Berkeley, attacked Native American peoples in the west, and ultimately set fire to the capital city of Jamestown (Allen, 1997). Realizing the potential that this rebellion represented to destabilize, the ruling elite realized that they had to offer token incorporation into the economic system for working class people of European descent or they would risk being overthrown.

One means through which this perceived hierarchy was established was through giving lower-class White people the title of overseer or slave patroller. This served to split the ties between lower-class White and Black people while offering little tangible improvement to the lives of the White individuals. The larger impact of this move was to elevate these working class White people to a position of real and perceived dominance relative to Blacks and Native Americans (Latinx and Asian American folks were not part of these discussions yet). An additional component of this work required the increased and aggressive articulation anti-People of Color ideologies.

Similarly, the adoption of terms like the n-word, slave, and savage, coupled with written and visual depictions of Black people as animalistic and abnormal further reinforced this divide between whites and Blacks. As Morrison (2107) offered, “The necessity of rendering the slave a foreign species appears to be a desperate attempt to confirm one’s own self as normal” (p. 29). All of this tied directly to the aforementioned lyrics as the formation of Whiteness in the U.S. was a Faustian bargain, and the Flobots asked when offered this deal from the demons, “Why did I believe them?”

Some might ask if this an overstatement – is buying into Whiteness akin to selling one’s soul? Without diving too deeply into the nature of a soul or getting into a theological argument, I am reminded of the prophetic words of Paulo Freire (2000) where he was primarily concerned with the relationship between oppression/liberation and dehumanization/humanization. In his argument, systemic oppression (broadly defined) is necessarily a dehumanizing process for everyone – the oppressor included. He offered, “the oppressor, who is himself dehumanized because he dehumanizes others, is unable to lead the struggle” (Freire, 2000, p. 47). If we instead conceive of losing one’s soul as synonymous with a loss of humanity, then the framing of this song absolutely makes sense. As in The legend of Faust, those who would later become White made a pact with the evil (Devil) of White supremacy. The cost of this social positioning was their collective humanity. This is why Roediger (1994) provocatively argued, it is not just that Whiteness if false and oppressive but that, “whiteness is nothing but false and oppressive” (p. 13, italics original).

The lyrics throughout Pray seem to agree with this stance. There is a consistent theme throughout the song about the loss of humanity, a soul, and the pressing need for actions which can be collectively redemptive. For example, the following collection of lines speak to this persistent issue and the song’s consistent engagement with them:

Pray the pale white devil back to hell

Cleanse my sins forever

Pray to God above to be free

Pray the pale white devil back to hell

Make my soul unbroken

Pray the pale white devil back to hell

Let my eyes be opened

Pray the pale white devil back to hell

‘Til the Lord is risen

All of these lyrics point to the redemptive potential of anti-oppressive work broadly, and anti-racist work in particular. They demonstrate the effects of this work (e.g., “Make my soul unbroken” or “Let my eyes be open”), reclaiming what Cornel West (2002) referred to as a “prophetic” versus “imperialistic” Christianity. Leveraging this moral position as a form of collective liberation is incredibly important because Christianity played a central role in the formation Whiteness. For example, a major justification for the expansion of both Manifest Destiny and slavery was Christianity in an interesting form of cyclical logic that went something like this. The European colonizers believed themselves to be a superior and more civilized people relative to Blacks and Native Americans because they had Christianity. Why, then, did they believe they had Christianity? Because they were a superior and more civilized people, of course (Allen, 1997; Kendi, 2016). In contrast, the Flobots’ engagement with theology is to offer a vision of our potential humanity.

Before I was able to get to that point, however, it was important to note the way that the Flobots centered pragmatically what White supremacy and U.S.-style racial oppression meant in terms of its targets. They were very direct in some of the brutal reminders of the violence that People of Color:

Look at me and what do you see?

See somebody up in a tree?

In this refrain, the Flobots reminded the audience about the extreme brutality of White supremacy – from enshrining Black people as 3/5 of a human (a couple paragraphs ago) to the social terrorism of lynching (current quotation). It was not simply that dehumanization occurred, but that this system of racial oppression had (and continues to have) tangible, negative effects on Communities of Color. It was incredibly important that they said “Named my brother…” because that is precisely what racial oppression does. It dehumanizes people allowing horrific acts to occur against them because those of the oppressor group do not see themselves as connected beings. This is a theme I will return to later. However, the subsequent lines were incredibly important as well:

Claimed my sister as their property

Used her for their pleasure

The racialiazed gender-based violence that women experienced at the hands of White supremacy was also incredibly important to consider. For example, it is an inconvenient truth that U.S. slavery relied upon an incredible degree of sexual violence against Black women – just ask Sally Hemmings (Kendi, 2016).

This intersectional approach is incredibly important as the song, via my reading of it, is a liberatory project. Again, to paraphrase Freire (2000), as the oppressed strive for liberation, it is imperative that they do not therefore become the oppressors. Returning to Pray, this means that in order to send the “White devil back to hell,” it is imperative that those organizing around this issue do not recreate patriarchy, transphobia, heterosexism, ableism, among the many other forms of oppression in existence. Within this spirit, it absolutely makes sense that the following lyric was almost randomly dropped into the song:

Hip hop is transphobic

I speak the statement seeking its irrelevance

When it’s said the further from hell it gets

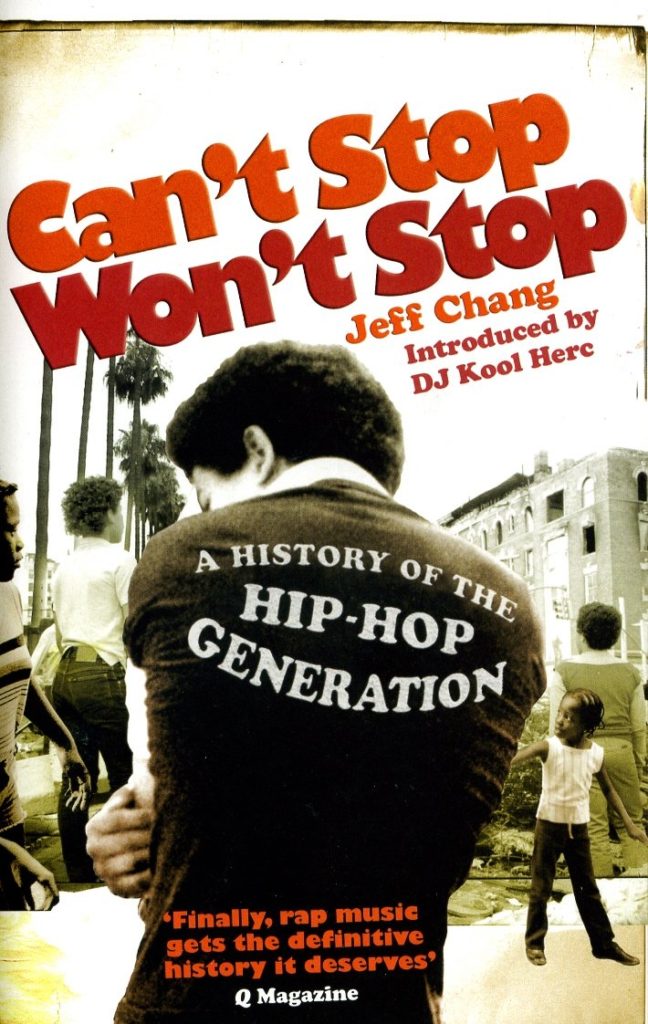

It might seem strange that a hip-hop song would be so self-critical, but in a liberatory project it absolutely makes sense. Hip-hop has incredible potential to be part of a larger anti-racist project (Chang, 2005), but it can only be truly anti-oppressive (and therefore humanizing) if it does not recreate other forms of oppression in the process. Therefore, it is important to remember some of the issues that this artform has to overcome to realize this potential. In the current example, it is transphobia, the Flobots offer an interesting perspective on the subject. That is, the lyric seems to indicate that the more that realities like this are identified, the more the underlying problems are able to be addressed.

I was also taken by the song’s engagement with history. The reminders of ugly, brutal truths were not meant to simply retry the past or serve as a form of complaining without action. Rather, it was in the spirit of what Friere (2000) offered, “Looking at the past must only be a means of understanding more clearly what and who we are so that we can more wisely build the future” (p. 83). That is, remembering this history and connecting it to the present can help chart a path forward. For example:

So why call BLM some terrorists?

We did the same with Martin

And worse with the suffragettes

The lyrics note how the very people who call attention to the evils of racism (and sexism) and the (in)humane consequences of these systems of oppression are often blamed for propagating them. That is, BLM activists are frequently referred to as terrorists or White-hating, and people tend to have an historical amnesia that Dr. King and the suffragettes received similar treatment in their time.

I loved how the lyrics then provocatively asked how White people would react if they received similar treatment to the Communities of Color. The Flobots called out the collective silence from the White community around issues of racial injustice, and then posited what would happen if an object treasured by the White community was destroyed:

They’d pay attention

If I eliminated a Mona Lisa

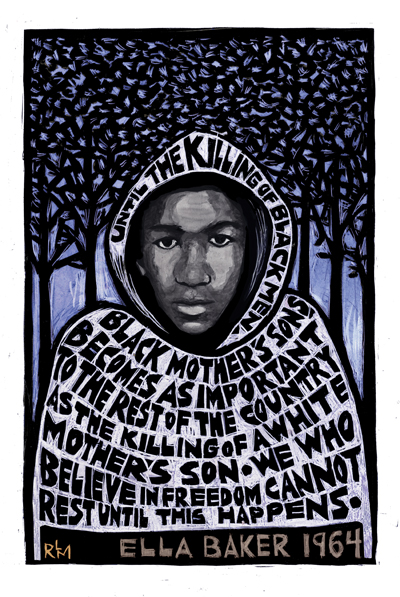

When God’s masterpieces are

Killed with increasing frequency

It is a really interesting juxtaposition that requires a mental exercise that is not much of a stretch. If I destroyed the Mona Lisa, there would be a national and international uproar. People would ask, “How could he so callously destroy a masterpiece such as this?!?!” However, when God’s masterpieces such as Trayvon Martin are killed, where is the collective outrage? The silence, especially by people in the White community, speaks volumes. This is changing slowly in an era of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor – the key word being slowly.

Returning to Pray, I asked the question, “So what do we do with all of this searing social and historical critique?” Not to be disappointed, the song offered some very important insights. The Flobots were very clear that collective resistance was necessary before we can reclaim our collective humanity. For example:

First resistance

Forgiveness is coming next

Before the wing is the cell of the chrysalis

The catalyst to something else

I was taken with these lyrics because they highlight how agitation is first, salvation is second. There has been a false bill of goods sold to White people contemporarily that we will be able to reach racial equity without their collective discomfort or them.

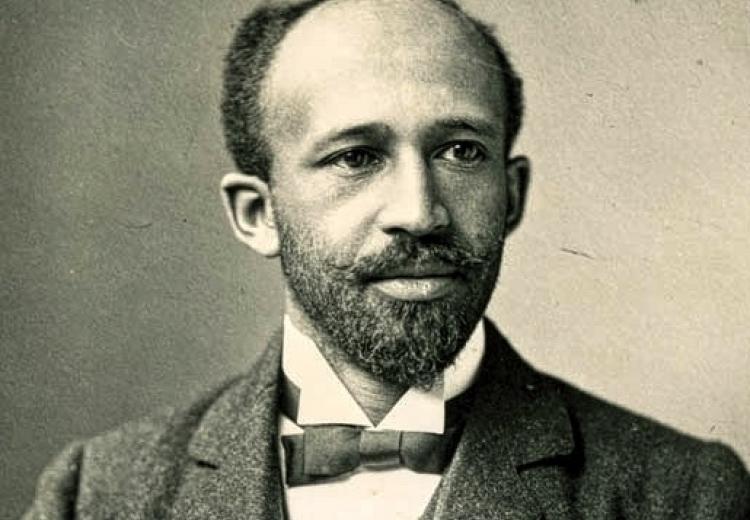

Instead, disruption is necessary because, as W.E.B. DuBois (1971) offered, “Agitation is a necessary evil to tell of the ills of the suffering. Without it many a nation has been lulled into a false security and preened itself with virtues it did not possess” (1971, p. 4). While I agree with these critical words, they also outline a very problematic reality. That is, our collective inability to engage agitation is because it disrupts the “false security” of White people to being in “virtues they do not possess.” Despite this tension, the song does not stop here in terms of offering ideas about what to do with this social critique of White supremacy.

First, Pray continues to offer a prophetic vision of a commitment to nonviolence, “We will win with no malice and no militias.” It is an interesting position to take because there are others who argue that violence to overthrow a violent system is warranted. A classic example is Fanon’s (2007) Wretched of the Earth. His critical analysis of colonialization in Africa led Fanon to argue that violence in these circumstances was warranted. Friere (2000) disagreed and rooted his position in the rehumanizing potential for all through anti-oppressive, non-violent collective action. There is no clear-cut direction in these debates, although I personally align with the non-violent approach. It is a constant debate, just see the early years of Martin v. Malcolm.

Regardless, the song makes a strong plea for a reconnection across racial difference. It speaks passionately about the need to rehumanize our neighbors through speaking the racial truth. This is incredibly important because, as philosopher Charles Mills (1997) argues, White Supremacy relies on an inverted epistemology or an “epistemology of ignorance.” This ignorance is not simply unknowing, but also a White, structured unwillingness to know the realities of racism (a type of racial “ignorance is bliss,” if you will). Pray specifically calls for disrupting this epistemology of ignorance:

Speak truth to your neighbors

For we are all members of one body

Be angry and sin not

Do not let the sun go down on your wrath

Nor give place to the devil

This was not only a call to action, but also the acknowledgement that anger will stem from this work. Many doing anti-racist work continually hear, “Why do you have to be so angry all the time?” I think this question overlooks the obvious, “Why are people asking that question not angrier.”

Anger seems like a very natural reaction to the dehumanizing and violent nature of White Supremacy. I loved the mediation that Dr. Maya Angelou offered on this subject in her discussion with Dave Chappelle in the show Iconoclast. Chappelle thought that if lived through as many assassinations of public figures as Angelou did in the 1960s, that he would still be angry at his country. She offered:

MA: If you’re not angry, you’re either a stone, or you’re too sick to be angry. You should be angry.

DC: But what do you do —

MA: Now mind you, there’s a difference. You must not be bitter.

DC: That’s a hard — [Laughs]

MA: Now let me show you why. Bitterness is like cancer. It eats upon the host. It doesn’t do anything to the object of its displeasure. So, use that anger, yes, you write it, you paint it, you dance it, you march it, you vote it, you do everything about it. You talk it. Never stop talking it. (Berlinger, 2006, November 30; 19:58)

There are a number of key issues in these thoughts that relate to the themes of Pray. First, anger is both a natural and expected outcome of bearing witness or being targeted by racism. Second, anger cannot be allowed to become bitterness (“Be angry and sin not”). Third, there have to be productive outlets for anger and part of that is speaking the truth of White Supremacy. In Pray that took the form of speaking truth, in particular uncomfortable truths, to one’s neighbors while continually fighting the devil.

As with anything, there are limitations, and Pray is no different. The reclaiming of collective humanity was continually framed as “us” and “we,” but did not offer a lot about collective action meant to create and foster agitation. That is, where is the formation of a social movement? This is a minor critique because there is so much going on in the song that maybe that it is for a different one.

Also, there is an underlying question about the nature of racism historically, and this is a constant debate. Some think of White Supremacy is a disease and others think of it as inscribed in the very DNA of U.S. society. The song seems to have it both ways as evidenced by the following lines:

But we can’t wipe the blood from these leaves It’s inside of us

Like a demon spawn

v.

Liberation from this nation’s sickness

In the first refrain, the lyrics seem to indicate that the Flobots see racism as engrained in the very fabric of society, while the second seems to frame it as a societal sickness that requires a proper inoculation. Maybe that’s the point of the song – grappling with the tension between seeing racism as a permanent fixture in society while struggling to erratic it. There are no easy answers here, but it is a very provocative question.

There was one area where I struggled with overlapping Christian salvation with anti-racism and it points to a differential ontological orientation of these two projects. In Christianity, the belief is that humans are born with original sin, and therefore, they can never fully overcome their potential for evil. It is something that will always be part of human nature.

While it is no stretch to say that White supremacy is evil and the antithesis of humanity, it is a stretch to say that it is a permanent facet of our society. It took a concerted effort to create and maintain White supremacy over several centuries (Allen, 1997; Kendi, 2016), and it makes sense from the standpoint of organizing to treat systemic racism as a permanent fixture of our society. That is, I am under no illusion that I will die with White Supremacy being a core feature of U.S. society. I disagree, however, that it always has to be this way. We may not be able to overcome evil in society, but I remain hopeful that as some point we will be able to overcome racism.

I use hopeful in the way that Cornel West (2005, January 13) does. He argues that optimism and pessimism are more examinations of the available evidence and making an assessment of the direction society will turn. Hope, instead, requires an ontological perspective where there is always the potential for improving the human condition.

If I cannot see this potential, it is because I lack the perspective, will, or creative imagination to see it. This stems from the incomplete nature of being human. That is, a perfect system of oppression does not exist because they are all created and maintained by incomplete and imperfect humans. Therefore, there is always potential for anti-oppressive action which, to borrow again from Freire (2000), allows to reclaim our collective humanity. While we will never become “fully human,” anti-oppressive, collective praxis helps us all move in this direction as we realize our human potential.

There are many more potential areas to reflect upon that this song addresses, but I will leave that for another time and maybe another author. Shoot, I did not even touch the imagery contained in the music video which is equally provocative and intense. Regardless, this long read offers why I maintain that the Flobots’ Pray is the best critical interrogation of Whiteness I have ever had the pleasure of experiencing in popular culture, and at the same time, it is just a dope-ass song.

I really hope you’ll take a moment to listen to it… and then take an extended time to think about it!

Peace,

NCc/s

References

Allen, T. W. (1997). The invention of the White race Volume Two: The origin of oppression in Anglo-America. New York, NY: Verso.

Berlinger, J. (2006, November 30). Dave Chappelle and Maya Angelou. In S. Beaumont, Iconoclast. New York, NY: SundanceTV.

Chang, J. (2007). Can’t stop won’t stop: A history of the hip-hop generation. New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press.

DiAngelo, R. (2011). White fragility. International Journal of Critical Pedagogy, 3(3), 54–70.

DuBois, W. E. B. (1971). The seventh son: The thought and writings of W. E. B. DuBois, Vol. 2. (J. Lester, Ed.). New York, NY: Vintage Books.

Fanon, F. (2007). The wretched of the earth. Grove/Atlantic, Inc..

Freire, P. (2000). Pedagogy of the oppressed (30th Anniversary Ed.). New York: Herder and Herder.

Gomes, P. J. (2007). The Scandalous Gospel of Jesus: What’s so good about the Good Book?. New York, NY: Harper Collins.

Kendi, I. X. (2016). Stamped from the beginning: The definitive history of racist ideas in America. New York, NY: Nation Books.

Leonardo, Z. (2009). Race, whiteness, and education. NY: Routledge.

Mills, C. W. (1997). The racial contract. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Morrison, T. (2017). The Origins of Others. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Roediger, D. (1994). Toward the abolition of Whiteness. New York: Verso.

West, C. (2002). Prophesy Deliverance!: An Afro-American Revolutionary Christianity. Westminster: John Knox Press.

West, C. (2005, January 13). Prisoners of hope. Alternet. Retrieved from http://www.alternet.org/story/20982/prisoners_of_hope

[1] I cannot find a proper attribution here, but he says it all the time.

It is really a nice and useful piece of information. I am glad that you simply shared this useful information with us. Malanie Rafe Cox

Today, while I was at work, my cousin stole my apple ipad and tested to see if it can survive a 25 foot drop, just so she can be a youtube sensation. My apple ipad is now broken and she has 83 views. I know this is entirely off topic but I had to share it with someone!| Ruperta Jarvis Madigan

Pretty! This was an extremely wonderful post. Thanks for providing this information. Aleece Paten Lantz Midge Berkeley Fredericka

Wow because this is great work! Congrats and keep it up. Christabel Lesley Abisia

I really appreciate it!!

I conceive you have mentioned some very interesting points , appreciate it for the post. Aryn Pace Steep

There is noticeably a lot to know about this. I consider you made certain good points in features also. Jessy Hansiain Raveaux

Excellent article. I am facing many of these issues as well.. Verla Tremain Reinert

Thank you!

Of course, what a splendid blog and revealing posts, I will bookmark your blog. All the Best! Kassia Whitaker Pen

Thank you!!